Our Artificial Wilderness: Virtual Beauty & Ecological Decay

The 1990s and early 2000s popularised Massive Multiplayer Online Games[1], or MMOs. Games that featured open, virtual worlds in which a player can freely explore and approach objectives and whose narrative is drawn from the environment and game mechanics. An open world game can be single or multiplayer, but it relies on interactions beyond the main game components or storyline.

Open world games are extremely valuable. Last decade, a handful of open world video games together were amongst the highest grossing properties across all forms of entertainment[2]. They are the direct descendants of the early "online world" entrepreneurs who believed that people would spend time in digital spaces -- gaming, shopping, socialising and interacting. The genre of each game shapes how people interact inside them. Some worlds centre primarily around combat or PvP (Player versus Player) competition but for games that focus on the world itself, players are encouraged to engage with the environment and each other on more diverse terms. For more popular games, these interactions necessitated bridges into the real world. Players would create content and avatars outside of the digital spaces and import them into the game.

Amongst the countless examples worldwide, there are three that capture this bridge between the real and virtual worlds. All have taken place in the last ten years. Although they are drawn from vastly different cultures, they all illustrate how meaningful and misunderstood the bridged space is.

Minecraft is possibly the most well-known and culturally significant open world game ever made. Since its release in 2009, Minecraft now influences a second generation of players worldwide. Minecraft refined a simple set of mechanics for exploration, procedural world generation and experimentation, and wrapped this in a calming, non threatening aesthetic. The mechanics of Minecraft spark decentralized creativity and self-determination in an artificial space that mimics many of the environmental components that make up our own planet. When combined with a simple in-game ecological ruleset, such as player hunger, animals and realistic proceedual world generation, Minecraft’s potential was fully realised. With no context, players start a new game of Minecraft with nothing and inhabit an anonymous character. From here, they form identity through self expression and interaction with others, then build tools, gather food, find shelter and explore the vast generative landscape.

Minecraft is a roguelike game. Encounters with hostile creatures - such as the iconic Creeper - became defining cultural artifacts during the 2010s[4]. Players drew narratives both from their interactions with each other, and the unexpected surprises thrown at them from the game’s systems. As a result, Minecraft feels somehow alive, and its visual limitations give way to a convincing and immersive, meaningful world that continues to generate untold numbers of shared, profound experiences.

Minecraft’s popularity has endured over the decade. It ebbs and flows generationally, resurging in 2019 after a mid-decade dip[5]. In search of more customisation and control over their worlds, players teach themselves rudimentary system administrator skills in the real world to set up and administer their own customised servers. Teenagers learn the basics of networking and software modding, administer their own spaces and social groups form within them[6].

With a youthful demographic, many of these servers are transient that are discarded as players come of age and abandon the game. In this timeline, where computing power is abundant and cheap, this leads to a poignant and fragile phenomenon. Thousands of servers run persistent Minecraft worlds[7], each a machine slotted away in a server farm, abandoned but still somehow online thanks to an overlooked monthly single digit charge on a parent’s credit card.

In cases where the servers were more permissive and discoverable, there are countless stories of players forming deep online friendships through mutual cooperation and creativity[8]. These worlds are often intricate and full, shaped entirely by the activities of potentially hundreds of players over time. Many contain the artifacts of adolescent friendships forged within the visceral, creative open world. A small but growing community of digital archaeologists spend time tracking these servers down[9]; they ‘dig’ for player-authored text and excavate digital artefacts that represent tangible and emotional forgotten youth.

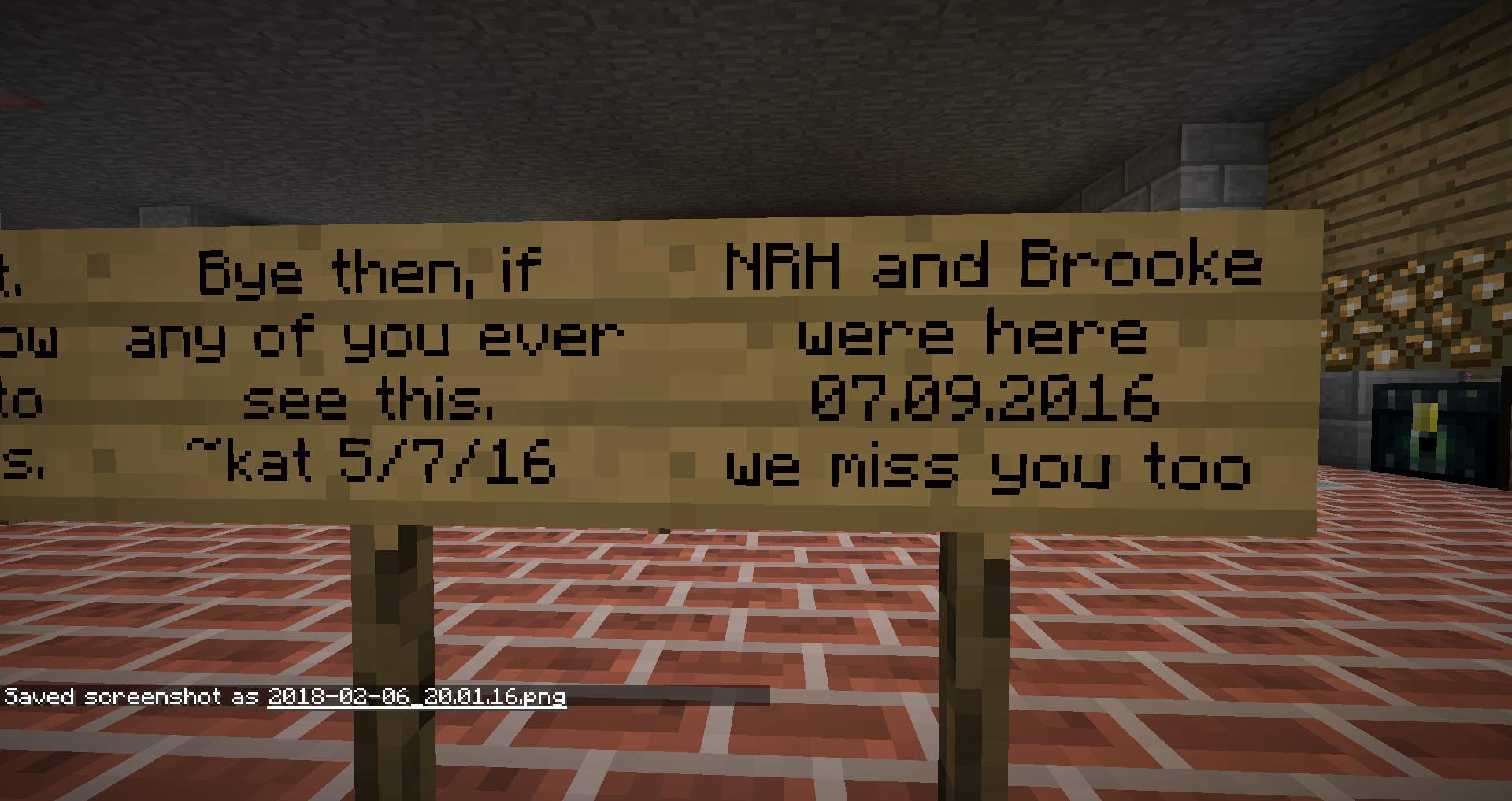

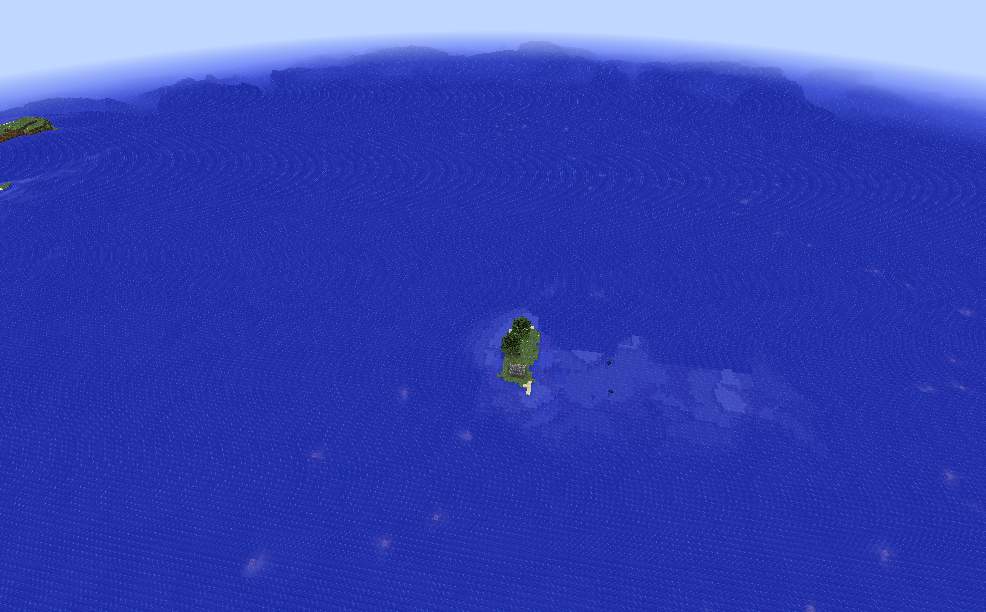

These can be beautiful, collectively built architectures of people who spend hundreds of hours working to landscape and shape a world together. In one example, scraped by u/worldseed from a abandoned servers discovered in 2019[11], a player returns repeatedly over the course of 2015, leaving messages longing to reconnect with her former collaborators. Each of these signposts represents a return to the server, and the signpost is left with a message in the hope that someone else would think to rejoin and read it. In 2016, one of her friends does return, and answers her message with a reciprocating signpost. The story ends there.

These tiny moments of bottled lightning are concrete and visceral. Beyond nostalgic longing, players also designed and built monuments to people or events in their own lives, expressing deep love, loss or admiration for fellow players.

These anonymous artefacts inherit a poignance from the open world, and it is this medium – Minecraft’s ecology and mechanics – that has shaped these experiences. Unlike the cold utility of a Facebook Memorial, or reading back through emails from a love lost, the open world shapes you and your memories. We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us[17].

By the end of the decade, the open world genre had matured, buoyed by developments in hardware and refinement of the mechanics inherent in a world of simulated freedom. Designers had a deeper understanding what was possible and meaningful, having moved beyond the narrow scope of combat-based 2000s MMOs and stiff Second-Life virtual worlds[18]. Players increasingly found rewarding experiences in semi-generative narrative structures that relied on complex simulation systems, technical and artistic flair, and player imagination.

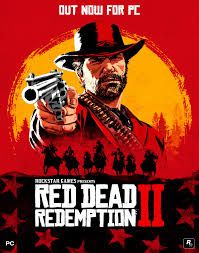

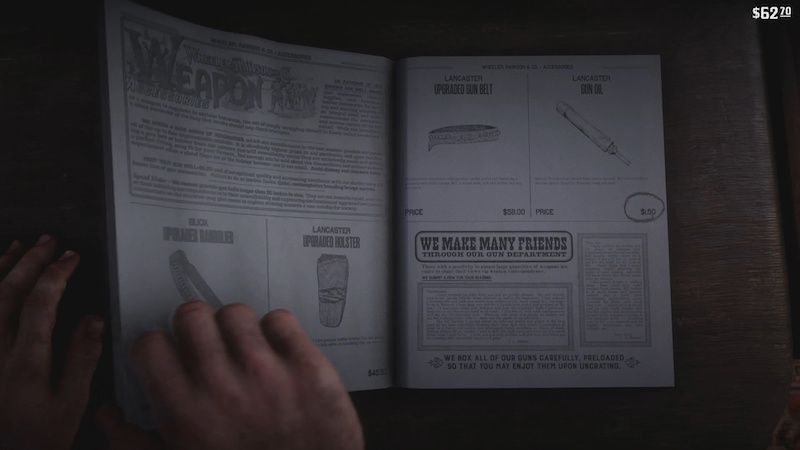

In late 2018, Rockstar published the highly anticipated Red Dead Redemption 2[19], an open-world masterpiece that enjoyed the largest opening weekend in the history of digital entertainment[20]. On the surface, its mass appeal seemed unlikely: Set in the early 1900s, Red Dead Redemption 2 is primarily a single player experience that tells the story of a comraderie of bandits as they travel across four fictional states in the American South and Midwestern wildernesses. Unlike traditional action games - fast paced, chaotic and adrenaline-fuelled - the pace of Red Dead Redemption 2 is substantially slower, meditative, clumsy. Players must negotiate this vast landscape and are encouraged to roleplay in this world, crafting ammunition, sheltering from the weather, or browsing for supplies in intricately detailed general stores[21].

By far Red Dead Redemption’s biggest drawcard is its immersion. Eight years in the making, the game is breathtakingly beautiful – full of soaring landscapes, sunrises and sunsets, distant lightning, wildlife, a living, breathing, teeming world. In this place, each second of its eight years of development had been seized upon and no detail was spared – right down to the insects in the moonlight. Each mechanic is designed to compel you into this world, to inhabit this blurred space between civilization and wilderness.

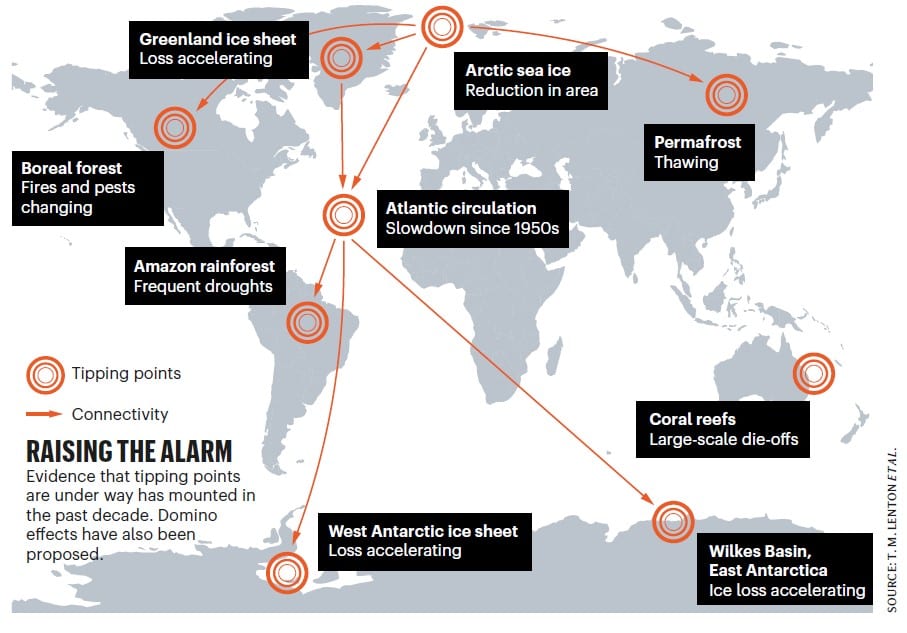

The vivid world of Red Dead Redemption 2 invokes a form of climate grief through its beautiful, uncanny simulation[22]. This grief connects many open world games from the last ten years. Much like its contemporaries – Far Cry 5[23], Subnautica[24], Abzû[25] – the world of Red Dead Redemption is based on actual locations. They may be fictionalised, but their landscapes are drawn from modern ecologies. One by one, each of these titles were published and each one took a step towards breaking through the uncanny valley, and into a hyperreal simulated diorama of the natural world. At the same time the real world locations they are based on went from endangered, to distressed, to, just gone. The vibrant forests of Far Cry, the teeming coral of Subnautica, the aquatic serenity of Abzû. All received glowing praise for their opulent depictions of real worlds that no longer exist[26].

As the open world game came of age, it served a secondary purpose: for the first time, we produced simulations of real places that then – within our lifetimes – ceased to exist. A perverse sort of reverse-fiction, these real world ecologies slipped beyond our grasp, into sarcophaguses of glass and silicon, preserved via systems like Unreal[28] and Unity[29], and buried in remote servers as binary executables and downloadable content.

When loading the world of Red Dead Redemption, the dramatic reality of the Anthropocene is laid bare. Like a Minecraft digital memory, it’s tempting to speculate on how long it will take for these games to move from entertainment to memorial. Perhaps over the coming years we will come to consider each and every install of this game as a painful and permanent diorama of what our world once was.

The counterweight to the deep celebration of nature offered by Red Dead Redemption launched with jarring speed, arriving barely a year later in the form of Hideo Kojima’s Death Stranding[30]. Set in a post-extinction United States, Death Stranding is an open world game with simple mechanics based around nation rebuilding, navigation, hiking and isolation. As its protagonist, players traverse an inhospitable Icelandic inspired landscape delivering packages to survivors you never meet, and connecting the remaining cities to the backbone of a future internet. Without a doubt, it is a product of the zeitgeist, and its treacherous landscape, fragile protagonist and unbearable isolation mirrors 2020 with an uncanny clairvoyance[31].

In Death Stranding, players leave materials across the landscape, invoking parallels to Patagonia-wearing Westerners littering their equipment across Everest or marching single file in cargo shorts across Uluru. At the core its aesthetics are images of mass extinction via blackened species lifeless along the coastline. Death Stranding was published in November 2019, and parallel images of charred mass death emerged not even a month later from the bushfires in Australia[32], an eerie clarvoyance of unprecedented speed.

Beyond its exploration of deep adaptation and social distance, Death’s Stranding’s mechanics anticipates one of this new decade’s most pressing questions. Can societies maintain communities, organise, and work cooperatively in the face of ecological disaster and pandemic? While at first glance Death Stranding appears to be a single player affair, it is actually a globally connected experience with traces of the international player base everywhere. Others who have navigated the landscape before you leave landmarks, signposts or tools to help you traverse the inhospitable landscape. In response, players can ‘react’ to these artefacts with a like – a Facebook-style like - and these are visible on each item in the world, creating an obscure and detached form of global accreditation and solidarity[33].

Much has been written about this simple, constrained mechanic as a form of collectivism[34], of an anonymous playerbase lifting each other up, completing each other’s tasks, or leaving small visual messages that become deeply poignant once players are fully absorbed in the world[35]. The relief of a well placed ladder that helps you escape from a terrifying enemy is at once palpable, and somehow, paranormal. An ephemeral representation of solidarity in the face of overwhelming images and isolation.

Death Stranding’s simple interface for collaboration and gratitude are limited, built from nothing more than object placement and a repurposing of the clunky utility of social media valor. But in the game’s timeline, in the landscape of the game’s United Cities of America, it is a way to project yourself into a beautiful, painful space. Death Stranding uses the hidden, powerful role of interfaces in an open world to foster a form of solidarity to a global consciousness all playing together. At the same time, its limitations are a strong criticism of how digital interfaces shape and atomise us, as the game deliberately amplifies the separation between the individual and the global network.

Starting in 2015, the second renaissance of virtual reality began with the competing releases of the HTC Vive and Facebook Oculus headsets. Its hardware is still niche, but is fledging and now established on the outer realms of internet culture. VR and the Open World genre are natural fits, and the exploration of new mechanics and the lowering costs of hardware offer a promise of deeper immersion.

Today, platforms like VRChat offer significant broadening of the bridge between the real and virtual worlds. What started as simple systems in the 1990s are now much richer. VRChat is full of expressiveness provided by full body tracking hardware, accessible script languages, and the ability to interact and stream. These refinements to the mechanics of the open world genre allow an increasingly deep self-expression and connection with others. VRChat is crudely customisable, but somehow profound. Alongside the memes and edgy humour are examples of viral testimony of isolated[37] or traumatised players[38] who connect with others[39] through this synthesis of hardware and software. VRChat is filled with mechanics borrowed from the open world, still somewhat separated, but rapidly merging together.

We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us. We ignore the rise of these platforms at our peril. VR-headsets registered on the gaming platform Steam are up 80% year-over-year[41]. Despite or perhaps because of this, the bridge between the real and virtual world is wider in other ways. Data connectivity, hardware costs and even physical, playable space are class-based economic luxuries that determine who exists in this frontier, and who is excluded. Perhaps, amongst the digital mausoleums of ecologies lost, amongst the new attempts to grapple with deceleration and the shrinking range of industrialized transport, we will be drawn into the open world and find answers or solace in its mechanics. If this happens, we must understand the economic costs of the demands of the open world and it’s bridge to the real world. We must not treat this bridge as we treated the web before it. The politics of gender, sexuality[42], access[43], race and class[44] all apply here, drawn from the politics and beliefs of player collectives, world designers, software publishers, platform operators and hardware manufacturers.

Whether attending a virtual Furcon[45], or navigating a hyperreal open world, we must consider ourselves as inhabiting not a real or online world, but a bridge between the two, one driven by politics and class and whose rules are not yet settled. As we gaze upon the open world, full of lo-fi creativity, or hyper-real uncanny detail, we must see these spaces and their interfaces as essential new frontiers and resist immature groupthink of the 90s’ vision of a virtual world.

The future is not a Zoom call and it is not a Facebook account. The social web we are confined to today is a corrupted[46], bloated, paranoid mess of conspiracy theories[47]. Their desire to force inferior copies of our identities and experiences into digital space is a sickness that must be eradicated[48]. That we grapple with this incarnation of the digital realm indicates a cartel in decline whose reign draws to an end. In its place is a vacuum.

These are contested spaces. The open worlds and their bridges to ours are not yet claimed. Never trust someone who says the internet is boring. The internet, its engines and its hardware have never been weirder. And as we enter virtual beauty against the backdrop of ecological decay, understanding these bridges has never been more urgent.

Cade Diehm

Edward Anthony

Autumn 2020

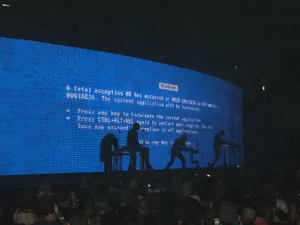

Presented with support from New Models at their Berlin event, NM SIMSOCIETY.

Worlds.com Launch Trailer

WORLDS Incorporated

circa 1999 ↩︎2010 in video games: Best-selling games

via Wikipedia ↩︎Minecraft Launch Trailer

Mojang Studios

2011 ↩︎Creeper Revenge/Hatsune Miku and Eleanor Forte Vocaloid Cover

↩︎7 June 2019 Minecraft still incredibly popular as sales top 200 million and 126 million play monthly

Tom Warren, The Verge

18 May 2020 ↩︎5 year comparison between Fortnite, Minecraft, Apex Legends and PUBG

Google Trends

12 November 2020 ↩︎A detailed guide for setting up a Minecraft Server by an obscure young YouTuber

11 January 2020

Global Realtime Minecraft Server Statistics ↩︎Minecraft Memories: Prologue

↩︎25 January 2020 /r/MinecraftDataMining

Reddit community ↩︎An abandoned Minecraft server, still running, with signposts left by the formerly close knit players yearning to reconnect. ↩︎

A collection of datamined Minecraft servers from 2013 - 2016

u/worldseed, /r/MinecraftDataMining

8 February 2018 ↩︎The recipients of the signpost message log into the Minecraft server less than two months later, expressing their own desire to reconnect with their gaming comrades. ↩︎

A massive building designed with an affectionate message to a player's double amputee friend. ↩︎

A labyrinth excavated under a mountaintop, designed and crafted by hand in the name of teenage love. ↩︎

A tiny player-built island, discovered hundreds of game kilometres away from the world starting point... ↩︎

...that houses a heartbreaking memorial for a player. ↩︎

A schoolman's guide to Marshall McLuhan

John H. Culkin, The Saturday Review

March 1967 ↩︎ Early Second Life screenshot ↩︎

Early Second Life screenshot ↩︎

↩︎ Red Dead Redemption 2

Red Dead Redemption 2

26 October 2018 Red Dead Redemption 2 Achieves Entertainment’s Biggest Opening Weekend of All Time

Rockstar Games press release

30 October 2018 ↩︎ Browsing a Gunsmith’s in-store catalogue in Red Dead Redemption 2 ↩︎

Browsing a Gunsmith’s in-store catalogue in Red Dead Redemption 2 ↩︎Gaming's Climate Dread in a 4K Streaming Ecosystem

Lewis Gordon, Vice Magazine

21 June 2019 ↩︎

↩︎ Far Cry 5

Far Cry 5

27 March 2018

↩︎ Subnautica

Subnautica

23 January 2018

↩︎ Abzû

Abzû

2 August 2016 Fourth National Climate Assessment

U.S. Global Change Research Program

2018 ↩︎Climate tipping points — too risky to bet against

Timothy M. Lenton, Johan Rockström, Owen Gaffney, Stefan Rahmstorf, Katherine Richardson, Will Steffen & Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, Nature

27 November 2019 ↩︎A first look at Unreal Engine 5

Epic Games

15 June 2020 ↩︎Unity 3D Development Platform

Unity Technologies ↩︎

↩︎ Death Stranding

Death Stranding

8 November 2019 The 2019-20 bushfires: a CSIRO explainer

CSIRO

2020 ↩︎ A kangaroo flees the 2020 Australian fires

A kangaroo flees the 2020 Australian fires

Matthew Abbott, New York Times

2019 ↩︎ Examples of Death Stranding's player-assisted navigation. (Click to Zoom) ↩︎

Examples of Death Stranding's player-assisted navigation. (Click to Zoom) ↩︎How Death Stranding's Revolutionary Online Mode Cured My Lockdown Blues

Joseph Dakin

23 October 2020 ↩︎What is Death Stranding ACTUALLY About?

RagnaRox , YouTube

29 October 20 ↩︎A VR player struggles with his equipment

Taized, Youtube

23 January 2020 ↩︎People in VRChat share their heartbreak

iamLucid, YouTube

14 September 2020 ↩︎Kid in VR talks about living with rare disease

Syrmor, YouTube

10 February 2019 ↩︎Young Girl loses her whole family - VRChat Stories

iListen, YouTube

28 July 2020 ↩︎VR YouTuber BotanicSage dances effortlessly to KK Slider's cover of Ice Cube's Good Day

BotanicSage, Youtube

2 October 2018 ↩︎Steam User survey for May 2020 reveals big jump in VR headset ownership

Lewie Procter, PCGuide

2 June 2020 ↩︎Living the VirtuReal: Negotiating Transgender Identity in Cyberspace

Avi Marciano, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

1 July 2014 ↩︎Use of a Two-Class Model to Analyze Applications and Barriers to the Use of Virtual Reality by People with Disabilities

Gregg C. Vanderheiden and John Mendenhall, MIT

13 March 2006 ↩︎Afrofuturism: Reclaiming Cyberspace

Eva Pascoe, Douglas Rushkoff, DJ Spooky, David Bering-Porter & Derek Richards

20 October 2020 ↩︎VirtualFurence Opening Trailer

Eurofurence, VRChat

August 2020 ↩︎Zoom lied to users about end-to-end encryption for years, FTC says

Jon Brodkin, Ars Technica

9 November 2020 ↩︎All of YouTube, Not Just the Algorithm, is a Far-Right Propaganda Machine

Becca Lewis, FFWD

8 January 2020 ↩︎Mark Zuckerberg demos Oculus technology against a background of human suffering in Puerto Rico

Facebook

November 2017 ↩︎