[1]On a twilight autumn morning in the middle of the 2020 pandemic lockdown, I pull open my ship’s navigation computer and plot the final jump to Sol. I feel a disassociation I commonly experience on a long-haul international flight, the sense of being in two places at once. In one world, I’m in Berlin, slumped at my home office desk in the pitch dark, shivering in the unseasonably cold morning air. In another, I’m flying a two-person spacecraft with my passenger, a close friend who has agreed to my persistent invitation to “come see home.”

We are playing the virtual-reality version of Elite Dangerous[2], a popular massive-multiplayer online space exploration game. We have been playing for four hours because we are traversing space back to our home solar system, across a stunning and physically accurate 1:1 representation of the Milky Way[3]. As I carefully plot a faster-than-light path through space, we gaze upon the alien constellations, dwarf stars and dual suns that we jump to along the way. Our path through the galaxy is depressingly devoid of life, save for the two of us and an ever-expanding (and violent) player-driven human colonization. We talk a lot, with the intimacy of a late-night road trip. My ship heaves like a truck at every faster-than-light jump. We can almost feel its vibrations.

Adjusting my VR headset, I glance again at the navigation computer and am surprised when our own, recognizable solar system becomes visible. The planets, moons and satellites of Sol are tiny specks against a sea of stars and black, but my ship’s augmented reality interface highlights them for us. Their names and orbital locations spark a weird familiarity, like pulling up a Google Street View of the neighborhood where you grew up. My passenger and I have talked for hours, but our conversation dies down as we draw closer to Earth. The space traffic around Mars is teeming, and although these are likely non-player characters, our relief at seeing human activity after hours in the isolating ink-black of deep space is palpable. Cutting through the silence, my passenger blurts out, “Mars is busier than I remember.” Given there are no spaceships in 2020, this makes sense.

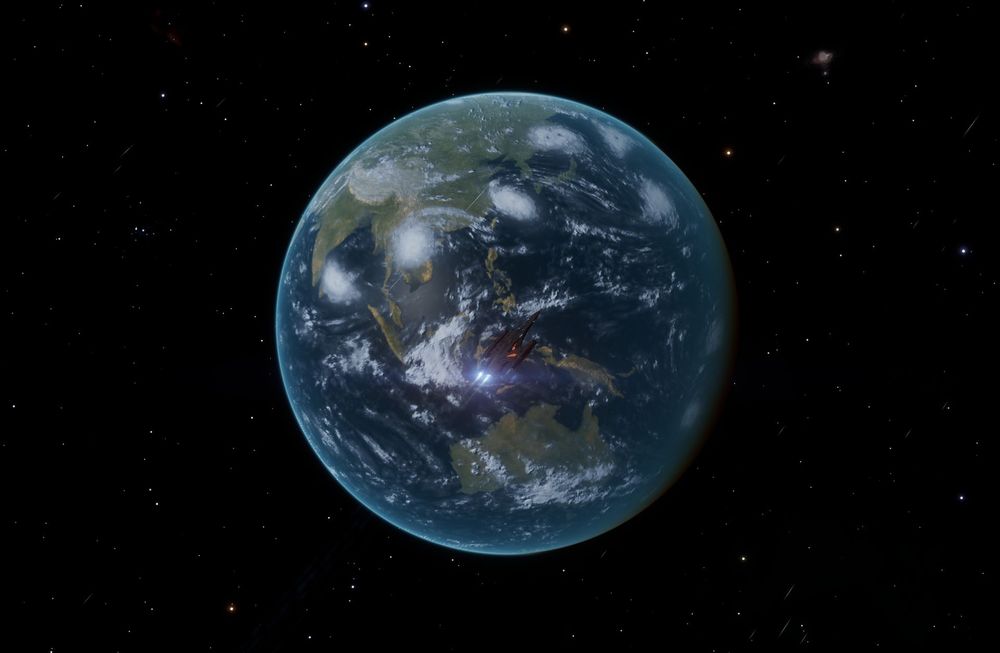

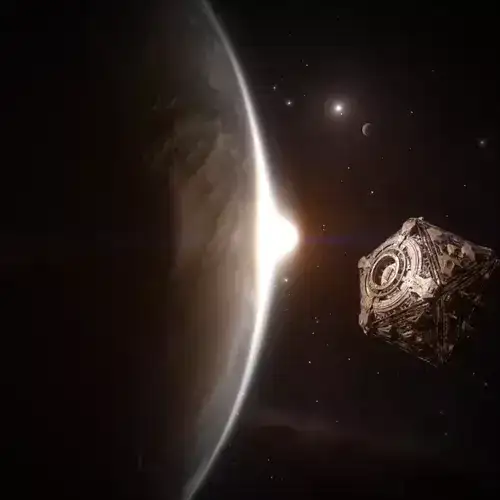

In Elite Dangerous, the game world is set far in the future, the year 3306, but the clock is synced to Coordinated Universal Time, or U.T.C. My passenger and I are coming home to Earth but also to a different millennium. We arrive in the shadow of the planet, right above the Baltic Sea. Before us is home, the Blue Marble—Earth. It is dark in the Western Hemisphere, and the glow of civilization at night is visible from this vantage point. Given the trauma of the recently locked-down pandemic world, I feel a strange comfort that the planet is safe in the future[4]. The physical world and this metaverse line up perfectly to give way to the para-real[5], and for a few ephemeral minutes, I am both here and there, dazed by the beauty of the artificial wilderness before me. The sun is rising in my apartment. I watch it rise from 45,000 kilometers above my own body, 1,286 years in the future. I am here and there. I can feel myself above me.

It is an eternity before my shipmate speaks: “I wonder if this is how astronauts feel the first time they see Earth.” A thought occurs, filling me with sadness. I realize that we are the middle children of human history—born too late to explore the Earth, too soon to explore the stars.

The overwhelming beauty of visiting Elite Dangerous’ future version of our solar system is famous among the game’s player base. Players who livestream on Twitch have broken down in tears in front of their audiences as they watch the sun rise from orbit upon returning to Earth or after tracking down the Voyager probe and hearing recordings of peace[8]. This is the appeal of the open world genre, where play and exploration mechanics mix with in-game social interactions in a beautiful and often hyperreal environment that can engender profound and unexpected interactions between players.

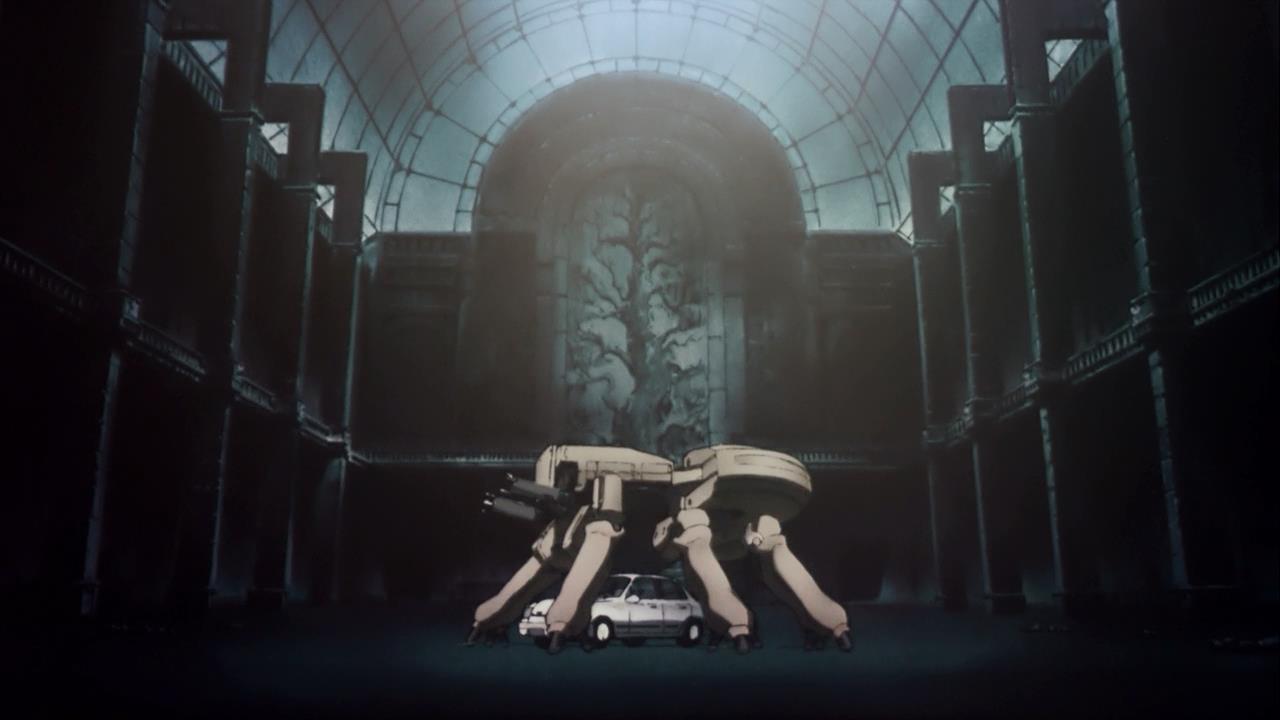

These experiences are also deeply bound to the social and personal lives of the players. As players come of age and abandon games targeted at younger audiences, such as Minecraft, the servers containing their worlds are often left behind and forgotten. But they remain online, in vast, always-on data centers that are full of the digital dreams of youthful players, awaiting connection requests that will never come. Dedicated online communities—such as the /r/Minecraft-Archeology[9] subreddit—have formed to discover and archive these abandoned servers. In the process, the archivists often uncover intimate remnants scattered across these spaces—memories and markers of flirtation, first loves, journals chronicling teenage loneliness, remote monuments of grief for lost friends. Elite Dangerous features large structures floating in the darkness of space, in which players can leave messages to memorialize deceased players or other people from their lives. It is not uncommon to come across one of these structures and see a lone player spacecraft drifting alongside it, quiet in contemplation.

Minecraft and Elite Dangerous are only two of the more celebrated examples of this kind of digital-born, game-based social phenomenon. There are many more— Elden Ring[11], Animal Crossing[12], Grand Theft Auto[13], World of Warcraft[14] —all, despite their commercial success, vastly under-appreciated touchstones of late 20th and early 21st-century cultural life. Central to the genre is the creation of immensely elaborate simulated worlds that contain countless details similar to ours, making them highly believable and appealing places to spend time. The complex narrative capability built into these worlds is key to their importance in our lives of as the middle children of history. For one thing, the capability satisfies a desire to explore the earth itself at a deeply troubling, atomized time, one of shrinking mobility, loss of public space, rising instability and the depredations of late capitalism.

When my colleague Edward Anthony and I first described the concept of the artificial wilderness in our 2020 essay of the same name[15], we articulated the role of the open world in a form of climate grief. Whether by design or not, the wilderness and its mechanics can be a barometer or reverse mirror of the damage wrought by the effects of human-caused climate change. The games, particularly those set in vibrant oceans, lush forests, untouched 19th-century American landscapes and similar environs, represent carefully crafted, opulent depictions of a younger planet, snapshots from long before the earth began succumbing to environmental ruin. As open worlds took steps towards breaking through into such uncanny valleys, they created dioramas of ecosystems too late to explore.

These artificial wildernesses are, of course, brought into being by insatiable, market-driven forces, the desire for new intellectual property, technological advantages and profit—a vulgar hunger fed by massive data centers, 3D-rendering farms, exponentially expanding computer storage and a never-ending cycle of consumer and professional hardware. Examples abound, but the release of the NVIDIA GeForce 4090 dedicated graphics card in 2022 marks a turning point in the appetite for the artificial wilderness[16]. It is a dedicated piece of hardware capable of visually simulating and rendering individual rays of lights to generate physically accurate shadows and reflections—a massive increase in graphics processing ability and also an over-the-top piece of hardware with electrical power needs substantially higher than previous iterations.

As the artificial wilderness assembles an anti-monument to the decline of our planet, it depends upon digitization as actual material, infrastructure that demands endless extraction and consumption of the same dying planet it memorializes. The middle children of history devour the real earth to fuel simulated versions fit for exploration.

Alongside the replica of our known universe, Elite Dangerous also sports a complex model of galaxy-wide human economic and political activity. These systems ebb and flow in real time, shaped by AI simulations and actual market forces, as well as by narratives from the game’s creator, Frontier Developments[18]. Markets and balances of power can be influenced over time through coordinated efforts organized by factions within the player base.

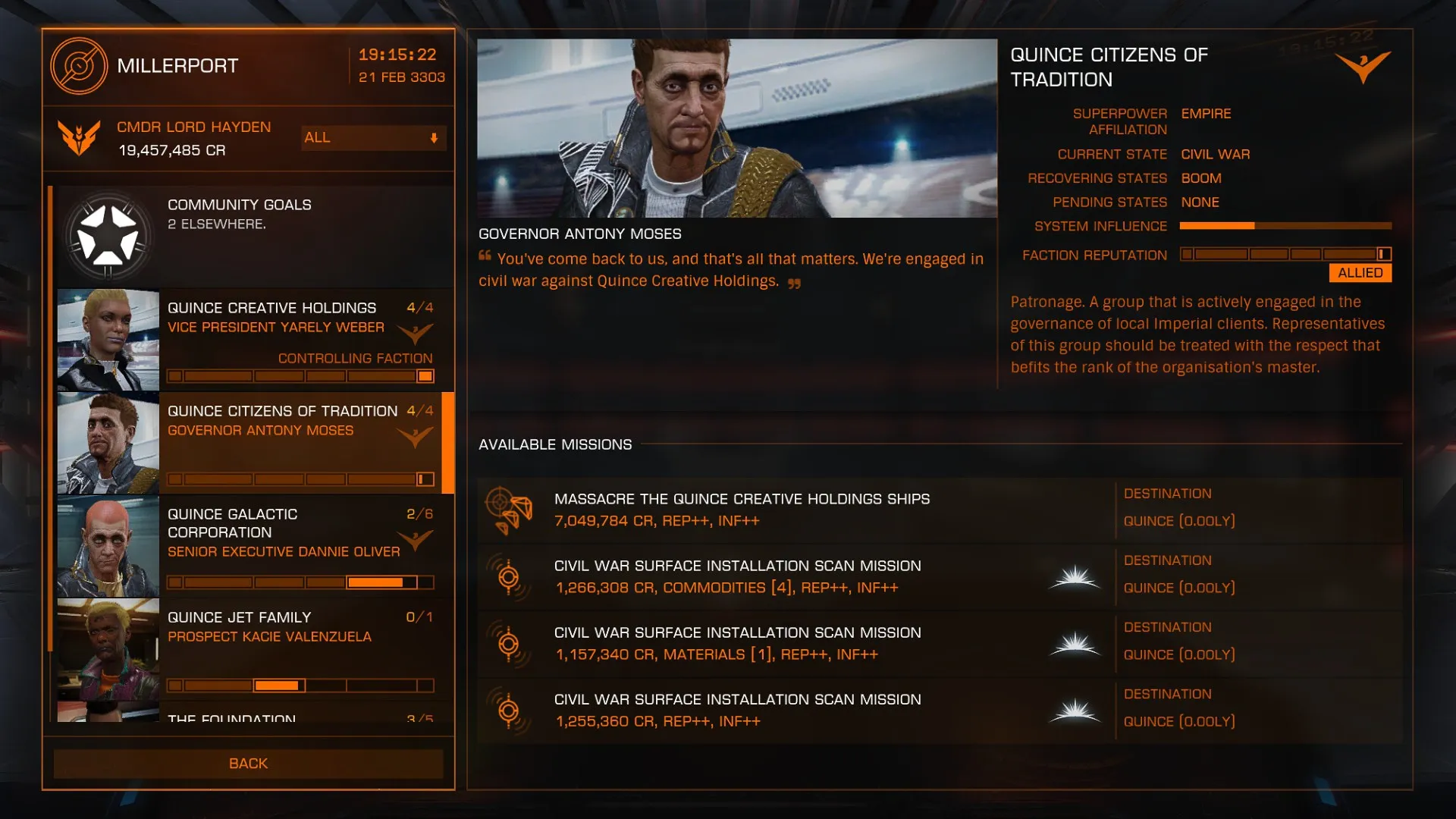

A few days after our visit to Earth, we logged back into the artificial Milky Way. My passenger, still affected by the para-real gaze upon the simulated Blue Marble, is keen to build a pilot’s profile and acquire a better ship to explore the vastness of space. We visit outposts and stations, scanning contract boards for lucrative job postings. Like all video game quest systems, the contracts on offer within the Elite Dangerous universe are partially determined by game mechanics and narrative. As we sift through glorified Uber Eats deliveries to destinations thousands of light years away[19], we see that the most lucrative jobs involve outright moral turpitude: human smuggling, environmental sabotage and assassination. Beyond player griefing[20]—situations where malicious, trolling players ambush and destroy unsuspecting or under-armed players—Elite Dangerous presents a universe full of malevolence. Despite great scientific and technological advance, the year 3306 is as riddled with suffering and inequity as 2020: In one particularly barbaric act, my player companion and I end up choosing to eject recovered human escape pods into the vacuum of space in exchange for a significant payout.

Of course, Elite Dangerous is built as dystopian science fiction, and inhumanity comes with the territory. But viewed against the games’ visual and environmental backdrops, the poetically beautiful re-imagining of our familiar and decaying world, the contradictions of such narrative begin to take on a political resonance. In a video entitled, “Minecraft, Sandboxes, and Colonialism,”[21] prominent YouTuber and critical theorist Dan Olsen details Minecraft’s mechanics of landscaping, crafting, hunting, resource harvesting and treatment of non-player character inhabitants. Seemingly benign and entirely rooted in the philosophy of play, these mechanics can easily combine to create situations that mimic similar acts of environmental and social brutality throughout human history, including ones happening right now.

This criticism cannot be levelled against Minecraft alone. Other games involve scenarios like the arbitrary slaughter of animals to craft rare equipment or the demolition of procedurally generated but often pristine environments for raw minerals, and the open world almost always absolves the player from consequences for these actions in service of play. No Man’s Sky[23], a flamboyantly colorful competitor to Elite Dangerous, allows explorers to land on planets teeming with life and extract minerals and chemicals with impunity to power their characters’ life-support systems. Players are generally free to shape the open world based entirely on their own needs, with no regard for the non-player characters—a stark simulation of the consequence-free vibe of capitalism.

As the artificial wilderness continues to consume the real, so too does the player consume this replacement digitization. The open-world genre reveals itself as a silicon sarcophagus holding a vast archive of environments lost. Perhaps the mechanics of extraction and destruction in realization of a player’s manifest destiny in fact complete the historical record—through gaming, the middle children of history are providing the most detailed testimony available[24] of just how this all happened to planet Earth. Or else they come to understand how to stop it.

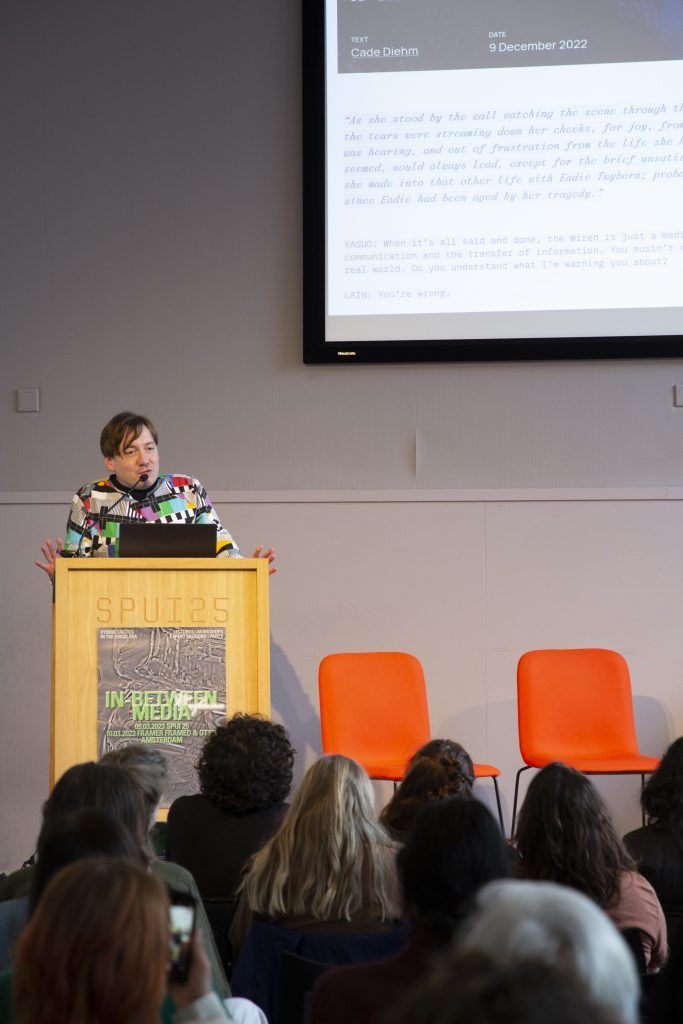

Cade Diehm

Spring 2023

Originally written for Ursula magazine's Glitch editorial column.

Buy the issue this essay appears in for €16,00, including shipping.

Originally published in

↩︎ Ursula Magazine

Ursula Magazine

↩︎ Elite Dangerous

Elite Dangerous

2014

The galaxy map of Elite Dangerous, supplied by the in-game fictious corporation, Universal Cartographics. (Click to enlarge) ↩︎Covid-19 - Timeline Of A Pandemic

Tom Compagnoni, Fairfax Media

10 April 2020 ↩︎ The Para Real: A manifesto

The Para Real: A manifesto

10 December 2022 ↩︎Gazing upon the Blue Marble in Elite Dangerous.

Photo credit: Cade Diehm ↩︎Twitch streamer Kolo Jones is brought to tears on livestream as she watches a sunrise over her residence in Cambridge, UK in Elite Dangerous. This VOD is edited for length.

~

Visiting Sol for the first time in Elite Dangerous

Kolo Jones, Twitch

27 October 2019 ↩︎ Voyager 1 and How To Find It | Elite Dangerous

Voyager 1 and How To Find It | Elite Dangerous

Ghost Giraffe, Youtube,

15 June 2017 ↩︎/r/MinecraftDataMining

Reddit community ↩︎Elite Dangerous Memorial For My Father (Cmdr Alexander Mckinnon)

Cmdr OrangePhoenix, Youtube

26 April 2019 ↩︎

↩︎ Elden Ring

Elden Ring

25 February 2022

↩︎ Animal Crossing

Animal Crossing

20 March 2020

↩︎ Grand Theft Auto V

Grand Theft Auto V

17 September 2013

↩︎ World of Warcraft

World of Warcraft

8 2004 Our Artificial Wilderness: Virtual Beauty and Ecological Decay

23 January 2020 ↩︎The RTX 4090 Power Target makes No Sense - But the Performance is Mind-Blowing

der8auer EN, Youtube

11 October 2022 ↩︎Within the vastness of Elite Dangerous’ interstellar world, sightseeing players find planets or systems with visually stunning landscapes or landmarks, and then often share these locations on Reddit and Discord. Here, I stand on a mountaintop as directed by a player from the broader Elite Dangerous community, watching a neutron star as it passes through the interlocking orbit of twin suns. It's like watching an eclipse. ↩︎

Frontier Developments is British video game developer founded by David Braben in January 1994 and based at the Cambridge Science Park in Cambridge, England. ↩︎

Elite Dangerous' Mission Board, displaying a number of mercenary jobs for player characters. (Click to enlarge) ↩︎

Elite Dangerous' Mission Board, displaying a number of mercenary jobs for player characters. (Click to enlarge) ↩︎Griefing: intentionally disrupting the immersion of another player in their gameplay

Wikipedia ↩︎ Minecraft, Sandboxes, and Colonialism

Minecraft, Sandboxes, and Colonialism

Dan Olson, Folding Ideas

23 August 2019 ↩︎Exploring a debris riddled industrial outpost on the outskirts of The Bubble. ↩︎

No Man's Sky

No Man's Sky

Hello Games

2016 ↩︎